Gerald Stanley’s acquittal will not be appealed.

Assistant Deputy Attorney General Anthony Gerein, the head of the Ministry of Justice’s public prosecutions office, announced the Crown’s decision on Wednesday, a few days before the 30-day appeal period’s deadline.

“There will be no appeal,” Gerein said.

The province’s top prosecutor was speaking in Regina and outlined, generally, the grounds for appeal before responding to questions from the media.

“The only reason you can appeal is if there was a mistake that was made, but that mistake has to be about the law and it has to be a mistake that made a difference or can be seen to have made a difference in the result,” he said.

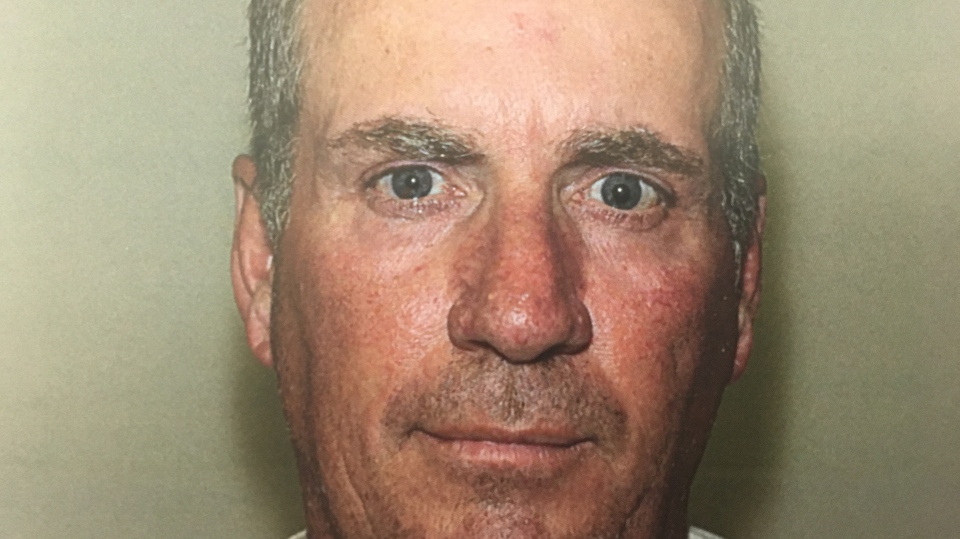

Stanley was found not guilty Feb. 9 by a jury in Battleford Court of Queen’s Bench. The 56-year-old farmer had been charged with second-degree murder in the August 2016 death of Colten Boushie.

Boushie, a 22-year-old Cree man from the Red Pheasant First Nation, was shot in the head with a handgun while he was sitting in the driver’s seat of an SUV that had been driven onto Stanley's property near Biggar, Sask.

It’s not disputed Stanley caused the death, the judge presiding over the trial, Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench Chief Justice Martel Popescul, told the jury during his instruction. The verdict was to come down to whether or not the jury found Stanley caused the death unlawfully.

The judge gave the 12 jurors three options before they began deliberations: that Stanley be found guilty of second-degree murder, that Stanley be found guilty of manslaughter or that Stanley be acquitted.

According to his instruction, to find Stanley guilty of second-degree murder, jurors had to feel the Crown proved beyond a reasonable doubt Stanley intentionally killed Boushie. To convict him of manslaughter, the jury had to feel the Crown proved beyond a reasonable doubt Stanley used a gun in a careless manner and had no lawful excuse for his use of the weapon.

Appeal grounds

“The Crown can only appeal if the court made an error about the law alone. The Crown cannot appeal a disagreement over the facts, the interpretation of witness evidence, or because a particular perspective leads to the opinion that the verdict was unreasonable,” Gerein said, speaking generally on appeals.

“Practically speaking, in reviewing a jury trial, the primary issues are whether the judge made an error, a legal error, as to procedure or on a point of evidence, or, as this was a jury trial, in the charge to the jury.”

Stanley testified during the trial he thought his handgun was disarmed when Boushie was shot, and his lawyer, Scott Spencer, argued the fatal shot was a hang fire — a delay between when the trigger is pulled and when the bullet fires. The farmer also said, as did his son, he believed someone from the SUV was attempting to steal an all-terrain vehicle from the yard, but two of the five people who were with Boushie the day of the shooting testified the group was looking for help with a flat tire.

Alvin Baptiste, the uncle of Boushie, said Wednesday he was disappointed but not surprised with the Crown’s announcement.

“I knew right away that we were going to be denied justice again,” Baptiste told CTV News.

The family has been vocal since day one of the trial, when no visibly Indigenous people were selected to serve on the jury.

Top prosecutor Gerein emphasized the Crown cannot appeal on any grounds outside legal error — including on jury selection or because of potential questions about the case’s investigation.

“Questions about the appropriateness of established procedures, such as how a jury pool is constituted or the peremptory challenging of prospective jurors, are matters for others,” he said.

Boushie’s family’s lawyer told CTV News he wrote a letter to Saskatchewan’s Attorney General Don Morgan on Tuesday, outlining what he believed were grounds for an appeal. He argued allowing testimony from two defence witnesses — specifically, two witnesses who testified they experienced hang fires — constituted a legal error.

“In my view, that evidence was inadmissible and should never have been heard by the jury. It was not relevant. It was an opinion, evidence provided by laypeople, and if it had any relevance whatsoever, the prejudicial effect substantially outweighed its probative value. It should never have gone before the jury,” Chris Murphy said.

One of the witnesses, Nathan Voinorosky, told court he once experienced a seven-second hang fire while target shooting, and the other, Wayne Popowich, said he’s experienced delays between seven and 12 seconds.

The testimony countered statements from a Crown gun expert, who said the longest hang fire he knows about was 0.28 seconds.

“That was the evidence before the court, and the laypeople extending that period was an important issue in the case and it should never have been heard,” Murphy said.

‘Not the end’

Baptiste, Boushie’s uncle, said the family will keep working for reform — specifically, reform to how Indigenous people are treated in the justice system — despite Wednesday’s announcement Stanley will not be criminally tried again.

“Even though my family has been denied justice, I’ll keep fighting for justice for future generations so that they don’t have to go through what we have to have gone through, that no family has to go through this again, ever,” he said.

The family will keep fighting for changes to the provincial Jury Act and the Criminal Code to allow for better Indigenous representation on juries, and the family will keep a close eye on the Civilian Review and Complaints Commission’s probe into the RCMP’s handling of the investigation, according to Murphy, the family’s lawyer. They also haven’t ruled out civil options, such as suing Stanley for wrongful death.

“This is not the end,” Murphy said.

Spencer, Stanley’s lawyer, did not respond to a request for comment Wednesday.

--- Angelina Irinici contributed to this report