Jae Blakley, like millions of others, is using services such as Ancestry DNA and 23 And Me to learn about his family tree.

His parents used a sperm donor to conceive him and it wasn’t until after his father died that his mother broke the news. The man who raised him wasn’t his birth father.

“I was terrified. It really shakes up your world when you find out your parent has not been your parent,” Blakley said.

The news prompted him to order from all the DNA services he could to maximize his results. He spit in a tube and sent the sample back.

Over the next few weeks matches started pouring in. He matched with a birth father and several half siblings.

In the 1980s, sperm donors were promised anonymity. Couples using the donors were sworn to secrecy and advised by doctors to not talk about it, even to their children.

“It’s really strange to think of a doctor being like, ‘Okay, the procedure is done and you can never tell anyone it happened,” Erin Jackson said.

It wasn’t until Jackson was 35 that she learned she, too, was donor conceived.

The Toronto native, now living in California, says her mom felt it was time she knew the truth.

Jackson says the realization made sense.

“It was an explanation for my face and maybe my personality.”

Jackson turned to DNA testing for answers on her family medical and genetic history.

“In my mid-thirties I felt like I had a really good grasp on who I was and this just blew everything up,” she said.

She hopes Canada will ban donor anonymity and notes other countries, such as Australia, have already taken that step.

Couples have the option to use donor sperm and men have the option to donate, but Jackson says donor-conceived people are the only ones who aren’t given a voice.

“I’m the only one that doesn’t have a choice and this affects me the most,” she said.

Sperm banks and adoptions were both once held to a level of secrecy, but DNA testing and increased access to information has changed that.

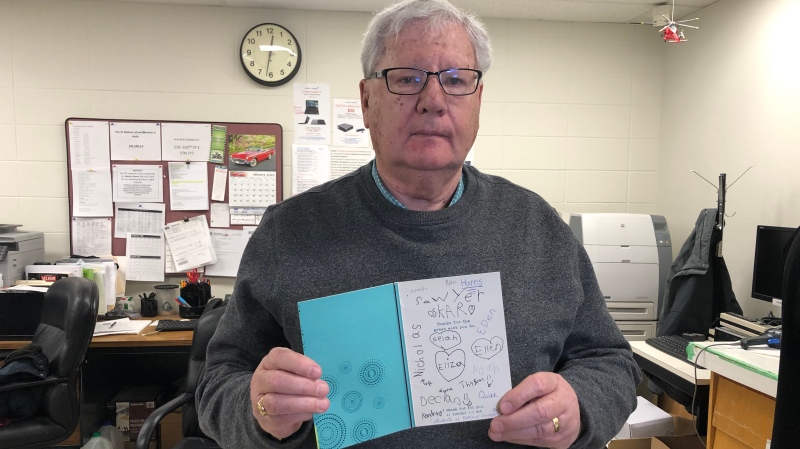

All adoption records are housed with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Social Services and it wasn’t until two years ago that changes were made.

The province has made it easier for adoptees and birth parents to request personal information. Before 2017, there were more hoops to jump through.

“The birth parents or the adoptees they would have to seek information from the other party, an approval, or consent to have that information released,” said Leah Deans, resource director with the Adoption Support Centre of Saskatchewan. That consent is no longer required, she said.

Even with increased access to information, a relationship isn’t guaranteed.

Blakley’s birth father, after some persistence, grew open to building a relationship.

“My dad was an abusive alcoholic, so finding out then that he wasn’t actually my dad gave me some hope thinking, well, perhaps I’m not now going down that same road,” he said.

While Blakley’s story had a happy ending, other donor-conceived people are left with a void.

Jackson’s attempt to connect with her birth dad led to a dead end.

“I was not greeted enthusiastically by him,” she said, but she has found peace at least knowing who he is.

She points people in similar situations to visit We Are Donor Conceived.