Historical research reveals that government officials tested tuberculosis vaccines on impoverished aboriginal people during the 1930s instead of fixing poor living conditions that spread the disease.

It's another example of how officials felt they could use aboriginal people as test subjects and looked for cheap solutions instead of fixing underlying problems, says Maureen Lux, a Brock University medical historian whose research is to be released in a book early next year.

"If (a vaccine) could provide resistance to TB, then we didn't need to deal with the economic situation that was causing the problem," said Lux, who first exposed the TB tests in a 1998 paper.

Last week, it was revealed that nutritional experiments were done on unwitting aboriginals in similar straits during the 1940s. The news has provoked widespread outrage and rallies across the country.

Lux, who specializes in the history of aboriginal people and the medical system, looked at conditions on reserves in the Qu'Appelle region of southern Saskatchewan in the early part of the 20th century.

"People lived in log huts," she said.

"They didn't have the cash for windows or doors. Living conditions were fairly crude."

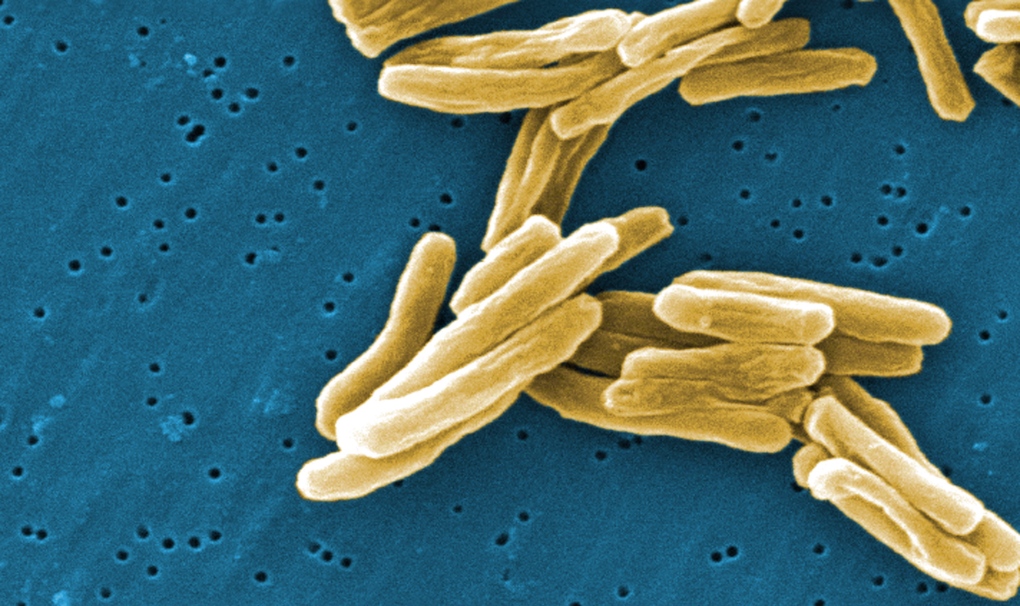

Tuberculosis was rampant.

In 1921, officials found that 92.5 per cent of aboriginal children tested positive for exposure to the infectious respiratory disease -- almost twice the percentage of non-aboriginal children. Overall health was so poor that the child mortality rate surpassed the birth rate.

Lux, whose research resurfaced in a report by the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network earlier this week, found that officials understood the link between health and living conditions.

In 1930, a showpiece settlement was built at the File Hills Farm Colony. Log huts were swapped for frame houses, new wells were dug, families were given chickens and garden seed and extra nutrition was provided to children and expectant mothers.

Tuberculosis death rates were halved. But the File Hills model wasn't followed.

"It was clear that with slightly better living conditions, tuberculosis could be dealt with," Lux said.

"But that's a fairly expensive proposition. The vaccine was a much cheaper alternative. This provided great hope for the Department of Indian Affairs and the National Research Council."

The vaccine had been previously tested on working-class children in Montreal, but researchers found it difficult to keep track of their test subjects. The Qu'Appelle aboriginals, who couldn't leave their reserves without a permit and who had high rates of infection, were thought to be just right for the job.

Between October 1933 and 1945, a total of 609 infants were involved in the tests -- half given the vaccine, half not.

Results were clear: nearly five times as many cases of TB among the non-vaccinated children. But the real lesson from the tests was the connection between dire living conditions and overall health.

Of the 609 children in the tests, 77 were dead before their first birthday, only four of them from TB. Both vaccinated and unvaccinated groups had at least twice the non-tuberculosis death rate as the general population.

"The most obvious result of the ... vaccine trials was that poverty, not tuberculosis, was the greatest threat to native infants."

The vaccine was judged safe and remains in use in many places today. Living conditions on reserves remained unaddressed.

"The trial was a success, but unfortunately the patients died."