REGINA -- Mike Bryant spends the days since his children were killed trying to keep busy.

But at night he struggles.

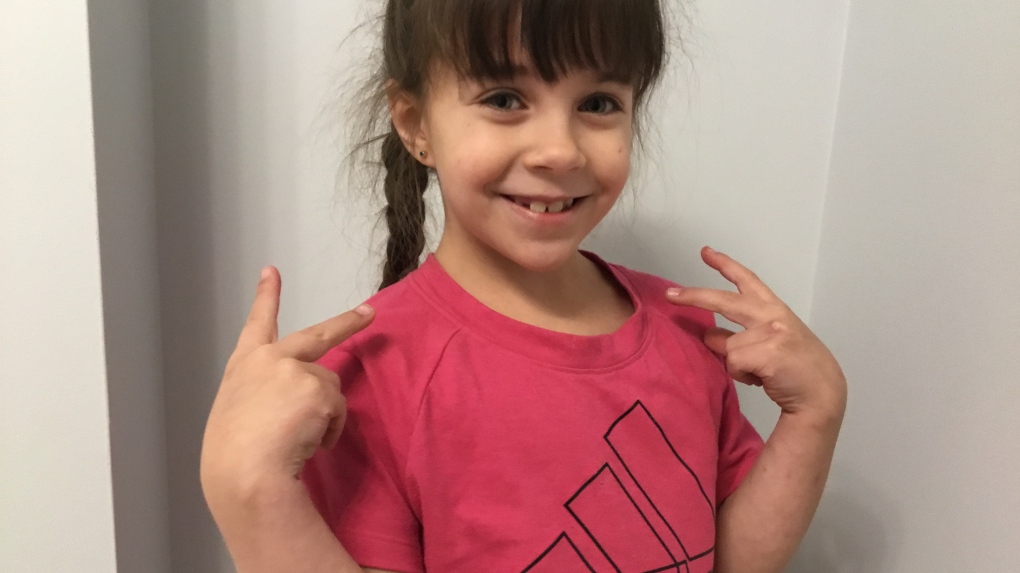

His mind races thinking of his kids: Tessa, 7, who loved animals and dreamed of becoming an RCMP officer; and his son, Wesley, 11, who aspired to work on his family's third-generation farm outside North Battleford, Sask.

Bryant considers his biggest accomplishment as a father was teaching his son, who liked riding dirt bikes, how to drive a combine and a tractor.

His children died last month in what was first reported to RCMP as a house fire in North Battleford. Officers who did more than 30 interviews during the investigation later told Bryant it was a murder-suicide.

Tammy Fiddler, his former wife, was responsible for their children's death.

"I didn't see it coming," he says. "To me, it's still a dream, but it's not."

Bryant says he and Fiddler, 39, were civil to each other and he didn't see signs something was amiss. "She had a plan for a very long time. That's all I got told."

Experts, citing how often risk factors are present, feel child and domestic homicides should be reviewed to understand what happened in the hope of preventing similar deaths.

"I do believe that we should, as Ontario does, review every case where family members are killed by someone who is supposed to love them," says Jo-Anne Dusel, executive director of the Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan.

Dusel belonged to Saskatchewan's first domestic violence death review panel, which produced a report in 2018 that detailed how the province struggles with some of the highest rates of police-reported interpersonal violence among provinces.

It contained recommendations based on risk factors identified in six homicides from 2005 to 2014.

During that time, 48 people, more than half of whom were Indigenous and included children, were killed during domestic violence.

The Saskatchewan Coroners Service reports that from 2015 to now another 32 people were victims of domestic homicides. Four of the perpetrators killed themselves.

Dusel says the government has sent conflicting messages about whether such deaths will be reviewed, something called for in the report.

"In the next couple of years, I do believe we could be -- and should be -- looking at doing that again."

Drew Wilby, an assistant deputy minister in Saskatchewan's Justice Ministry, says the department hopes to have a decision by the report's three-year anniversary.

Dr. Peter Jaffe is a psychologist and director at Western University's Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women and Children in London, Ont. He says domestic death reviews are important to do on an ongoing basis.

That way, experts can look at how particular trends, such as a downturn in the economy or the COVID-19 pandemic, might impact domestic homicides, he says.

"When a plane goes down, you can't bring back the passengers, but we all wait to all see what happens when they find the black box.

"Domestic homicides and child homicides are no different."

Michelle Weber, executive director of the West Central Crisis and Family Support Centre in Kindersley, Sask., says the region is an energy hub, and staff see a rise in interpersonal violence when the oil-and-gas sector slumps or agriculture takes a hit.

Last December, a well-known couple in the town died in a murder-suicide. RCMP say David Gartner, 66, shot and killed his estranged wife Elsie Gartner, 64, before taking his own life. Police said they weren't aware of domestic violence.

Weber says living with a high risk of violence is a reality for families in the area, which has no safe bed space and a prevalence of guns and drugs.

A government spokesman says the coroner's office will review the police findings to determine whether to hold inquests into the Gartner or Bryant cases.

Bryant says he might look for answers later, but for now he's coping by talking to friends and family.

"You just gotta keep holding your little ones close to you at all times," he says.

"Make sure you love 'em and tell 'em that you love 'em."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published July 26, 2020

If you or someone you know is in crisis, here are some resources that are available. Crisis Services Canada (1-833-456-4566 or text 45645) and Kids Help Phone (1-800-668-6868 or text CONNECT to 686868) offer ways of getting help if you, or someone you know, may be suffering from mental health issues. If you need immediate assistance call 911 or go to the nearest hospital. The Centre for Suicide Prevention is a place where resources on suicide prevention can be found.