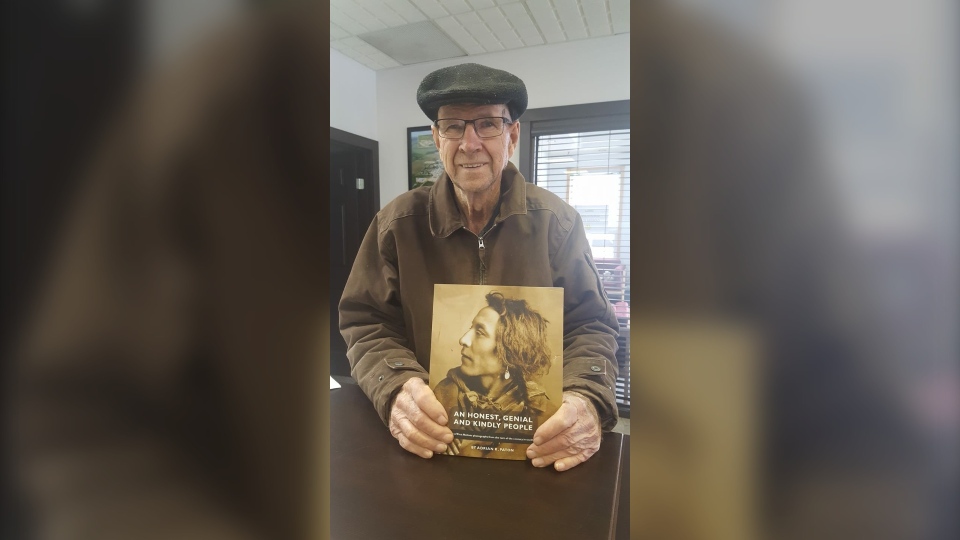

SASKATOON -- A historical photo collection of First Nations in Saskatchewan by Adrian K. Paton is being preserved and passed on after his death.

Val Guillemin, Paton’s daughter, says most of collection is from the broader community and has been collecting historic photos for 30-40 years.

“But more lucky then finding the photos was finding the people, the Indigenous people, who actually knew the stories behind those photos because that’s what makes them come to life,” Guillemin said.

As a non-Indigenous person, Paton has always been interested in First Nations people and made an effort to obtain as much information and details as possible to go with the photos, according to his website.

He interviewed other historians and First Nations people and decided to create a book with their stories as he felt it was important to share the photos.

“If it weren’t for him I think the history behind them would basically have been lost,” Guillemin told CTV News.

The pictures in his book “An Honest, Genial and Kindly People” are mainly from Moose Mountain and the surrounding region, an area that is now called southeast Saskatchewan. The book was released in 2018 and has sold 2,000 copies.

“He’s not trying to interpret them or put his own twist to them. It was just to tell the stories that he had been so fortunate to hear from Indigenous people who knew their rich history.”

In 1993, Paton established the South Saskatchewan Photo Museum which holds his entire photo collection.

When photography became more prominent and photos of Indigenous people were taken from a settler perspective they weren’t flattering, said Audrey Dreaver, lecture and program coordinator at First Nations University of Canada.

The photos in Paton’s collection show a more accurate depiction of how First Nations peoples lived.

She says the photos taken in a natural setting in their lifestyle is a “really powerful glimpse” into the kind of things they were interested in and how their clothing was connected to their culture and beliefs.

Historical information was also gathered for photos in the collection which add importance and context to the accuracy of First Nations stories.

“And I know that those photos have been used to connect and identify ancestors that have passed away,” Dreaver told CTV News.

She says she knows people who saw an ancestor for the first time and who they knew existed, but didn’t have any images of them.

Guillemin says she is working with the University of Saskatchewan to help guide her on the appropriate thing to do with the photo collection and Indigenous artifacts.

“The biggest thing my dad wanted for all of his photographs was for as many people to see them as possible. That’s what he wanted.”