CTV News is heading ‘Behind the Badge’ for an in-depth look into three specialized units of the Saskatoon Police Service.

Part one, below, looks into the internationally recognized Saskatchewan ICE Unit, which investigates child pornography offences in the province.

----------------------------------------

Photos of 14 girls line the wall.

They’ve been in that spot, directly across from the desk, for nearly three years. Their faces can’t be identified to the public, so the photos are hidden behind sheets of white paper during our visit.

We’re stepping into the world of Saskatchewan’s Internet Child Exploitation — or ICE — Unit.

Each photo shows a victim in the Russell Dennis Wolfe child pornography case. Cpl. Jared Clarke stares at their faces every day. They are there each time he looks up from his computer.

“They stare back,” he says, looking at the girls.

His colleague Det. Const. Shannon Parker knew three of the girls before she joined the police service.

She was a high school teacher in the city. She didn’t know the girls were victims until she joined the police and was assigned to the case.

She helped identify the three.

“That was quite upsetting and hit close to home,” she says, looking down.

Team of 12

The Wolfe case has consumed the ICE Unit for more than three years and is one of 12 to 20 cases ICE investigators work on at any given time.

The unit is made up of 12 RCMP officers and police from Saskatoon, Prince Albert and Regina. There are three forensic technicians, a provincial coordinator and eight investigators. Clarke is one of the investigators and has been on the job for five years.

He tells us that the investigations are categorized in two ways: reactive and proactive. Reactive investigations are launched when inappropriate behavior or files are reported to police by parents, computer repair shops or companies like Microsoft or Skype.

Proactive investigations include the online trading of child pornography through file-sharing networks.

“The same place people go to get illegally downloaded movies, there’s also an abundance of child pornography on there,” Clarke says from behind his desk. He shares a small office with another investigator on the third floor of the Saskatoon police station.

Going undercover

Part of proactive investigating includes going undercover online, posing as either a pedophile or a child or underage teen.

Clarke says when he first began undercover work online some users could tell he was a police officer.

“Try again, pig,” he recalls one user writing to him.

He says he’s since learned the lingo and how to let the other user drive the conversation.

He now travels abroad to train other officers on effectively posing online.

When he has a few spare minutes in his work day, Clarke goes undercover online. He logs on to his computer and opens up a website. It’s filled with conversations, links to download photos and video, and various chatrooms.

“There are rooms dedicated to the sexual exploitation of children. They're never going be shut down. There are hundreds of people in there at any given time,” he explains, scrolling through usernames that include ‘PedoM47,’ ‘Nauti_GRNDPA’ and ‘Seed4Young.’

Within minutes, Clarke is chatting with a user who claims to like incest and teens. The two talk about their day, their sexual preferences and if they are ‘active’ — or, actively abuse children.

“The people here are looking to chat with other like-minded people and either talk about how to abuse children without getting caught or come here to trade images and videos they already have… and even arrange to commit sexual offences against live victims,” Clarke explains.

He traces the man back to Oregon, which is out of his jurisdiction, but notes arrests in Saskatoon have been made from this particular site.

Next, Clarke opens a map of local IP addresses that have been flagged in the last three months. Six markers appear — each representing a hub people in that area that could be uploading or downloading child porn.

“I can't think of anything more horrific to view than child porn,” Clarke says. “I've got a family. I've got young kids at home. You put it in a box. You separate home from work and that's what motivates you to keep doing this job.”

The “significant” increase in workload and content keeps the unit motivated, he adds.

‘Forever changed’

In 2011 and 2012, the ICE Unit laid 60 charges. That number jumped in 2013 and 2014 to 156.

So far this year they’ve responded to 374 complaints and investigation referrals. The content is getting worse, Clarke says. The crimes are more violent and the victims are younger.

Parker, a digital forensic examiner, becomes emotional when she speaks about her work.

“Coming into the ICE Unit I don’t really think I knew what I was in for,” Parker says. “Violating babies, and sexually assaulting and raping babies and toddlers and five and six year olds and eight year olds — I didn’t realize those things were going on and after seeing those things I'd say I'm forever changed.”

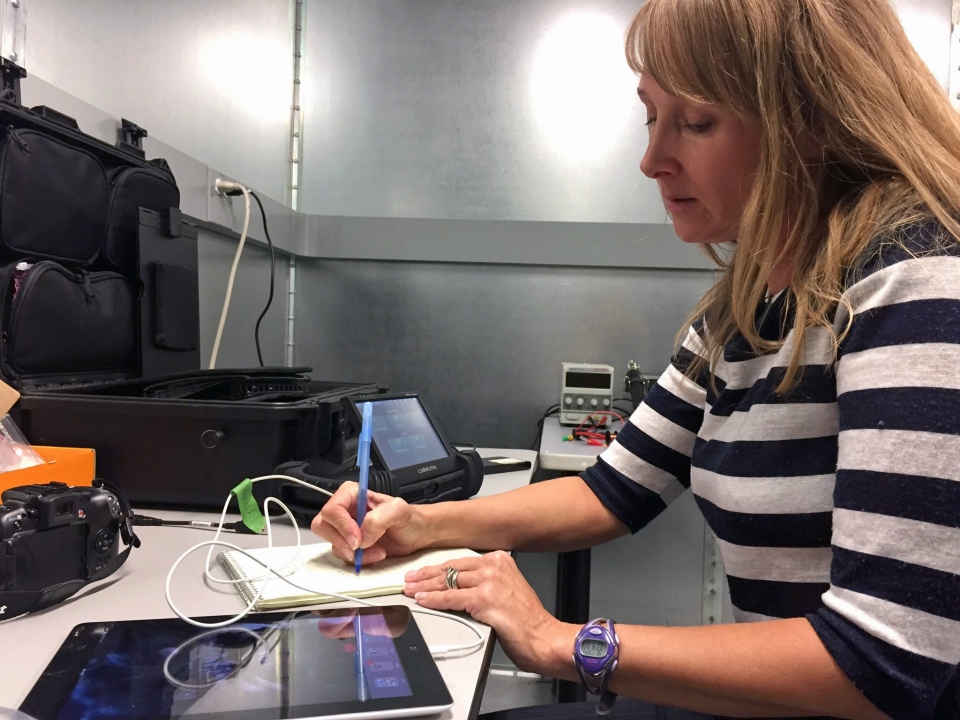

Parker analyzes devices that are seized by investigators. She sorts through electronic data and extracts files relating to the investigation, which can take anywhere from one day to one year, depending on the amount of data.

At times, she’s sorting through the equivalent of 16,000 books.

While speaking with us, Parker is extracting data from an iPad that’s been seized. The work is done in a special sealed area called a Faraday room, which prevents all electronic fields from entering or leaving the room.

“The main idea here is, when we seize mobile devices, we don’t want the devices to be connecting to the network. We don’t want people to be accessing their devices,” Parker says after closing the room’s massive metal door.

She also uses special equipment to crack encrypted devices if needed.

What’s discovered when the code is cracked is disturbing.

“I have a six and seven year old at home and I think the reason we all do (this) is because we care about kids and rescuing kids,” Parker says, with tears in her eyes. Her voice is shaking.

“It’s hard to see those things, but at the end of the day the reason you do it is because you know you’re making a difference.”

The most difficult part of her job is not taking her work home with her, she says.

Tough but rewarding

Clarke agrees the job can be difficult and take a mental toll, but he says there are “safeguards” in place for the unit.

Members check in annually with a psychiatrist, and counselling is available, he says. Talking about specific cases with colleagues makes a difference.

Both Clarke and Parker credit their colleagues’ dedication and expertise for the unit’s success. The drive to save the victims keeps the team going.

“That chance to rescue a kid. Just knowing that you're making a difference and you’re pulling a kid out of a bad spot. It's extremely rewarding work,” Clarke says.

Work he says will never end on cases the team will never forget.

Still looking

The ICE Unit has so far laid more than 20 sex-related charges against Russel Wolfe, but they’re still working to identify two victims in the case.

Wolfe’s trial, which is scheduled for May, will be the province’s first child pornography case tried by a jury.

The ICE Unit will never stop looking for the unidentified girls, Clarke says. The team wants justice for each and every victim.

----------------------------------------

Catch parts two and three of ‘Behind the Badge’ Wednesday and Thursday on CTV News at Six.